I once watched a conference by philosopher Denis Dutton who argued that humans have some sort of programmed drive to appreciate and do “things well done”. He was trying to explain why humans, in spite of their great cultural diversity, all have a conception of beauty.

I don’t think I agree with him at all, but I enjoyed the conference. He went through the evolutionary role of such traits, how it possibly related to mating rituals and how individuals obtain pleasure from their own “thing well done”.

Being happy about what one has done equals being proud of oneself. Being happy about something collectively done well equals being proud of that collectivity. Therefore, being proud of your team, group, religion, sect or country might seem something ingrained and not at all negative.

Unfortunately, patriotism has nothing to do with being proud of any good deed or accomplishment. As I understand patriotism (about which there is little conceptual consensus), it is a manifest expression of nationalism. One is a patriot when one manifests his or her pride for his or her country/nation or national identity. Nationalism is the conscious sense of national identity, or a deeper sense of belonging related to having been born somewhere.

Nationalism is born out of many different and differently interest-invested factors. The State needs its citizens to feel a minimum sense of belonging to the nation in order to govern. It also needs it in order to rage war against another nation and obtain a minimum level of approval from citizens. On the other hand, people are impelled to feel such sense of belonging when they, as a group defined by their national belonging, are hostilized or even threatened (or killed).

World history up to now has only strengthened this sense of belonging, or “local solidarities”, with endemic and acute wars, prejudice, discrimination and the wider phenomenon of Imperialism.

The other side of this coin is xenophobia. As a group of people feel impelled to support each other for having been born inside the same territory (whose frontiers are politically, not naturally, defined), the same group might feel impelled to hostilize those born outside it.

In any circumstance, nationalism and patriotic attitudes emanate from the worst aspects of our History as a species. It is not different, in nature, from other types of discriminatory and sectarian behaviors.

It seems pretty obvious that assuming a position against oppression and social injustice will result in supporting a few national interests, not necessarily ours: whenever a stronger army attacks the innocent civil population of any country, that is something I stand against.

Sports patriotism, however, is something I simply cannot buy. Its pinnacle has been the Cold War and its athletic expression, the Olympic War. Because two empires disputed their hegemony, athletes were thrown in the arena to represent (in a literal theatrical manner) their nations and fight.

Athletic competition, which should be anything except a battle or a fight, became nothing but that. Laymen from all parts of the world watched games they had no hint about, no possible way of understanding rules and tactics, just because one player (or team) was wearing one national uniform and the other, another national uniform.

This attitude has done nothing for humanity except feed its most destructive and perverse behaviors – be they innate or learned.

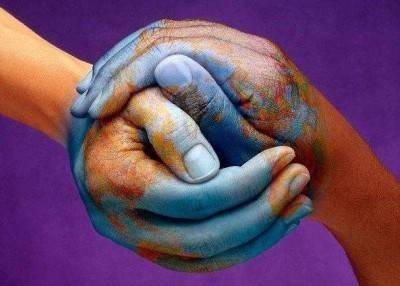

All this considered, how do we balance the need we all have for some sort of belonging and local solidarity and a cosmopolitan, politically and philosophically better way of approaching culture and society?

There is no easy answer. At some level, athletes from the same country should unite in defense of their interests (and not against athletes from another country). As Brazilian athletes, we share common enemies and obstacles. We share corrupt federation leaders, the Brazilian Olympic Committee, the politicians and other sports decision-makers who have since forever been responsible for our hardship.

We also share the need to carve a social role in society for ourselves as a group, and that requires us to see ourselves as a group united by certain common interests.

That does not mean that we need to take action towards such union through emotional and irrational calls for patriot pride. Again, this would be a civilizatory step back (I may be abusing this expression, or maybe not).

By the way, I wear the Brazilian uniform in my powerlifting international championships to honor the person who gave it to me: Dragos Doru Stanica, weightlifting head coach for the Brazilian team. He is from Romania. He has been the most successful coach in the history of Brazilian Olympic strength sports, having now obtained the best ever position in weightlifting with Jaqueline Ferreira. Long ago, when I was just starting in powerlifting, he called me a “Viking warrior”. I try to live to his expectations – not to some abstract ideal notion of a country I never felt I truly belonged to.

Answering Craig Calhoun’s question, yes, it is time to be postnational.

Some links and references:

Calhoun, C. “Is It Time to Be Postnational?” in Ethnicity, Nationalism, and Minority Rights, edited by Stephen May, Tariq Modood and Judith Squires (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

http://www.cabdirect.org/abstracts/19961808651.html

http://www.cabdirect.org/abstracts/20013040246.html;jsessionid=BF428F5B87F42B8A72A3CEEF40BC926A

http://www.policymic.com/articles/8712/olympics-2012-brings-out-the-world-s-patriotic-spirit

http://www.online-literature.com/chesterton/all-things-considered/7/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patriotism

MARILIACOUTINHO.COM – idéias sobre treinamento de força, powerlifting, levantamento de peso, strongman, esportes de força, gênero e educação física. Ideas on strength training, powerlifting, weightlifting, strongman, strength sports, gender and physical education.

A vida é pentavalente: arranco, arremesso, agachamento, supino e levantamento terra. Life is a five valence unit: the snatch, the clean and jerk, the squat, the bench press and the deadlift.